Students partner with Baltimore community members to measure ‘forever chemicals’ in local waters

Reposted from UMBC News: https://umbc.edu/stories/measuring-forever-chemicals-in-baltimore-waters/

On a sunny and unseasonably warm Halloween this past fall, a group of costumed UMBC students strolled the banks of the Inner Harbor in Baltimore. The costumes were in good fun, but the spirit driving them to the city that day was more scientific than spectral: They were there to check on samplers they had installed around the harbor to measure the concentrations of certain chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, in the water.

On Halloween, from right to left, Alvin Bett, an undergraduate student working in Blaney’s lab, Hamidi, Siao, and Leigh Auth, a boat captain with the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore who helped the group access the trash wheels to install their PFAS sensors. (Image courtesy of Siao)

On Halloween, from right to left, Alvin Bett, an undergraduate student working in Blaney’s lab, Hamidi, Siao, and Leigh Auth, a boat captain with the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore who helped the group access the trash wheels to install their PFAS sensors. (Image courtesy of Siao)

PFAS are used in a diverse range of products, including cleaning products, clothing, and fire-fighting foam, and have earned the nickname “forever chemicals” because of the way they persist in the environment. There are growing concerns about the health effects of the chemicals, and in recent years there have been efforts to eliminate PFAS from some consumer products and regulate their concentration in drinking water.

The UMBC students’ work to measure PFAS in Baltimore Harbor is one of the first projects aiming to get an understanding of how much of the chemicals are found in the waters around Baltimore and where they might be coming from. Margaret Siao, a master’s student in chemical engineering, took a lead role in the work as part of the ICARE program, which links researchers and Baltimore community members on environmental projects around the city.

Donya Hamidi, an environmental engineering Ph.D. student, also took part in the project, which served as a test case for a larger project she is working on, seeking to expand the utility of innovative passive samplers to measure PFAS in any water source.

“I’ve lived in Baltimore most of my life,” says Siao. “The harbor is a big part of the city, although many people don’t go out on the water. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to look at the water quality.”

PFAS are everywhere

There are thousands of different PFAS chemicals. Because of their widespread use and resistance to degradation, they are found throughout the country in the water, soil, air, and food, and in the blood of humans and animals.

Exposure to some forms of PFAS has been linked to a range of health problems, including decreased fertility in women, developmental effects in children, reduced immune function, and increased risk of cancer and obesity.

“The PFAS issue just gets more and more complicated by the day,” says Lee Blaney, the environmental engineering professor who leads the lab where Siao and Hamidi work. He notes the EPA recently released an initial risk assessment for certain PFAS found in biosolids, which are a byproduct of wastewater treatment and are sometimes applied to agricultural land as fertilizer. “It’s a big, far-reaching issue.”

Partnering with the community

Blaney is an expert on PFAS, and as concerns about the prevalence and potential health effects of the chemicals have grown, his lab has been a leading partner with Baltimore community members who advocate for and are responsible for the quality of the water.

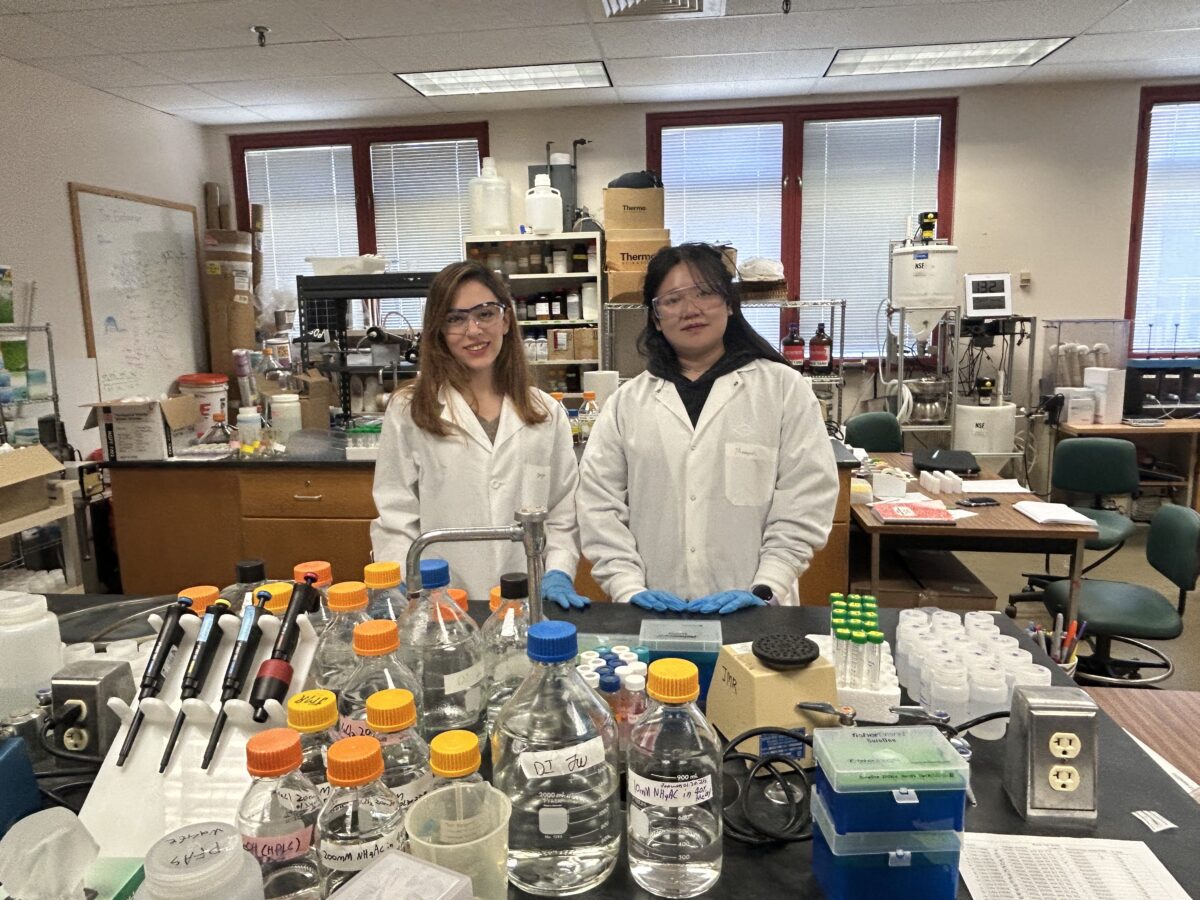

Hamidi (left) and Siao in the lab where they analyze samples for PFAS concentrations. (Image courtesy of Hamidi)

Hamidi (left) and Siao in the lab where they analyze samples for PFAS concentrations. (Image courtesy of Hamidi)

Siao’s ICARE project was a partnership with the United States Geological Survey Maryland-Delaware-D.C. Water Science Center and Blue Water Baltimore, a non-profit organization with the mission to restore the quality of Baltimore’s rivers, streams, and harbor. Blue Water Baltimore shared their knowledge of the harbor and area waterways and their connections with the community, while lab members shared their expertise and will share their PFAS data once it has been analyzed.

“PFAS is a hot topic, so Margaret’s project is really good timing,” says Barbara Johnson, who was Siao’s mentor at Blue Water Baltimore. “I think her data will be very useful for us in helping the public understand what PFAS are, for example just understanding how many different kinds there are. Margaret has taught me so much about PFAS.”

As part of the field work, Siao and Hamidi also sampled water at the outlet of the Patapsco Wastewater Treatment Plant in Baltimore. That partnership arose when Mohammed Almafrachi, who works as an engineer for the Baltimore City Department of Public Works, became interested in the PFAS issue and sought out a local expert.

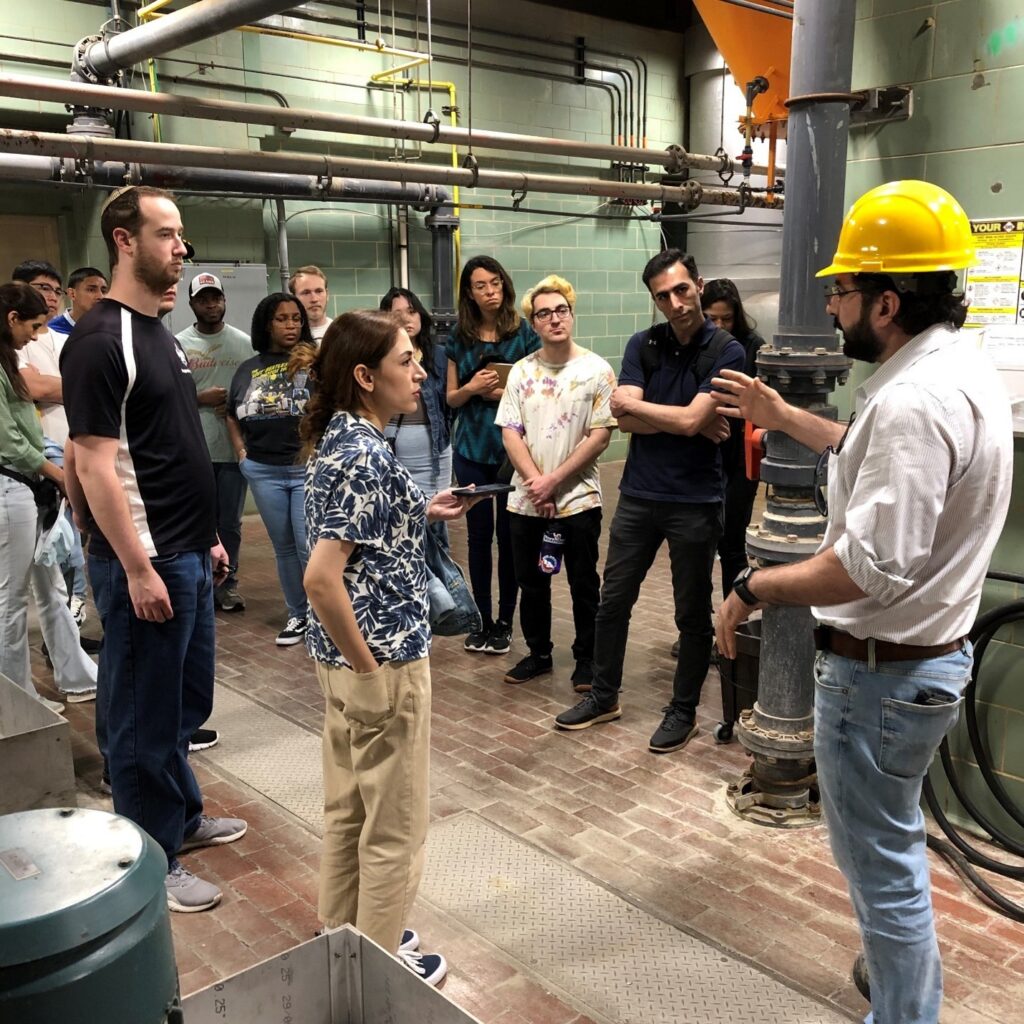

“Last year, I found Dr. Blaney’s name on the internet. I drove to the campus, found his office, and he was there. I introduced myself as an engineer at the city of Baltimore, and we sat down and started talking,” Almafrachi says. From that conversation grew not only the collaboration to measure PFAS at the wastewater treatment plant, but also a tour of Baltimore’s largest drinking water treatment plant that Almafrachi gave students in Blaney’s class on environmental physicochemical processes last spring. Almafrachi said he was happy to provide students with a window on a real-world workplace where their skills might one day be applied.

“If you have not gone to the field, then you are not yet a full engineer,” says Almafrachi. “We can talk about theories and textbooks endlessly, but the field is where you really test your skills.”

The value of field work

Almafrachi (right) led a tour of the Ashburton Filtration Plant, Baltimore’s largest drinking water treatment plant, for students in Blaney’s environmental physicochemical processes class. (Photo courtesy of Blaney)

Almafrachi (right) led a tour of the Ashburton Filtration Plant, Baltimore’s largest drinking water treatment plant, for students in Blaney’s environmental physicochemical processes class. (Photo courtesy of Blaney)

Siao and Hamidi agree with Almafrachi about the value of field work. They installed their PFAS samplers at three of the four trash wheels around Baltimore Harbor—personified contraptions named Mr. Trash Wheel, Professor Trash Wheel, and Gwynnda the Good Wheel of the West that collect floating trash and keep it from dirtying the harbor. To get to the trash wheels, they took a flat-bottomed wooden boat, “more like a floating platform with a little cabin,” Siao says.

“Almost every time we collected a sampler, we saw something new or unexpected, for example algae growing on the sampler, and we had to figure out what was going on at that particular site,” says Hamidi. The team’s work and the measurements they collected and are currently analyzing will serve as a foundation for future studies about PFAS in the local environment.

Both Hamidi and Siao say they valued the teamwork of their trips, and the chance to meet people in the community impacted by their research.

“If you are stuck in a lab all day, it’s easy to forget why you’re doing research,” says Siao. “This project gave me a chance to interact with people outside of academia, to learn about what’s important to them, and to learn how to communicate about science with them, which is a really important skill.”

Posted: April 3, 2025, 1:59 PM